LONDON’S ai. GALLERY HAS A MISSION – TO FOSTER A MUCH-NEEDED ARTISTIC DIALOGUE BETWEEN THE EAST AND THE WEST. HERE, THEY EXPLAIN HOW THEY ARE MAKING THIS HAPPEN.

Operating out of a contemporary gallery space in East London’s Spitalfields, A.I. Gallery are approaching art with a suitably contemporary outlook. Their goal? To encourage a healthy East-West dialogue within London’s art scene.

The gallery platform and curatorial project space champions emerging artists, especially those of South East Asia – now, they’re moving part of their operations to Cromwell Place to further their mission. Ahead of their inaugural Cromwell Place shows in 2021, we caught up with ai. Gallery’s Director, Anne-Marie Tong, to hear her insights into South East Asian art.

Hi Anne-Marie. Can you tell us about the ethos behind ai. Gallery?

ai. was founded in 2015 as a project space, and evolved into a gallery for early career artists – including collectives and research platforms. We aim to foster dialogue and to challenge the notions of the East and West. In doing so, we seek to champion South East Asian artists, amongst others. Most have furthered their studies in the UK – and the majority are women.

WeiXin Quek Chong, eatingcake.1, 2018.

Each country and each artist’s own experience within a country is highly localised and layered - Gallery

Why do you think it’s important to foster an East-West artistic dialogue, as your gallery aims to do?

The rhetoric of the East-West dichotomy is a longstanding one and, as a gallery, we are encouraging discussion around such constructed binaries.

Your latest exhibition, Nameless. echoes, spectres, hisses, focuses specifically on South East Asian artists and voices.Can you tell us a little about it?

Nameless. echoes, spectres, hisses was our inaugural online viewing room, conceived pre-lockdown. It features a mixture of sound and video, short film works, with each work being supported by a curator essay. The exhibition offers an entry point to thinking about locales outside of the UK – where our gallery is based – and brings into question placemaking within South East Asia.

The six works were curated by a research platform called XING, and investigate the region’s physical and political geography through sound: they include Benjamin Tausig recording the streets of Bangkok's Ratchaprasong district in revolt, Pathompon Mont Tesrateep’s environmental soundscapes of Thai jungles and collective mourning, and Sung Tieu utilising an alleged sonic weapon heard in Havana, overlayed with visuals of the Mekong Delta where once American-led psychological operations broadcasted the cries of ghosts of dead Vietnamese soldiers.

Artists in nanny states are self-censoring, particularly when dealing with ethnic minorities, politics and religion - Gallery

What themes do we see across the spectrum of South East Asian artists?

There’s an incredible diversity and range of topics represented throughout their artistic practices, including post-colonialism, post-independence nation building, post-dictatorship, cultural identity, memory, diaspora, spirituality, mythicism, socio-politics and globalisation – to name just a few. However, there are challenges in grouping together South East Asian artists, because each country and each artist’s own experience within a country is highly localised and layered. There’s so much complexity within the region that it simply renders itself unsuitable to a transnational and interdisciplinary overview.

How would you describe the contemporary art scene in South East Asia?

The overall contemporary scene is still much in its adolescence, meaning it’s still being shaped. The rise of South East Asian art correlates with increased affluence in the region, and there is a need to look at South East Asia as one market. The main hubs, those with effective arts ecosystems, include Indonesia – places like Jakarta & Yogyakarta – as well as the Philippines and Singapore.

WeiXin Quek Chong, (a cloud of foxes is not a dragon), 2020.

In your opinion, who are key artists from the region, past and present, to consider?

Key established artists to know include Thailand’s Prasong Leumang, Indonesia’s Nyoman Masriadi and Pacita Abad from the Philippines. These artists are now part of the international art world – you’ll find them at auction houses, representing their home countries in major art centres and being exhibited in regional biennales.

What is something that is often overlooked when considering South East Asian art?

There are two things. The first is that artists in nanny states are self-censoring, particularly when dealing with ethnic minorities, politics and religion. The second is that – with the exception of certain countries – there is a lack of adequate funding towards rigorous institutional programming and nurturing artistic discourse. That’s led to a reliance on small independent spaces, not-for-profit selling platforms or public-private models to act as catalysts or thought leaders. They hold the key to the region’s future.

How has South East Asia’s history informed its artistic landscape?

The artistic landscape of the region is marked and influenced by several factors. On the one hand, each country has been historically overshadowed by the great empires of nearby India and China. On the other, they have been colonised by a variety of different nations, all of different cultures and languages: the French in Vietnam, the Dutch in Indonesia, the Spanish in Philippines, or the British, Dutch and Portuguese in Malaysia. This gives South East Asia, on one hand, a background of shared influences – but, on the other, entirely differing influences.

The rise of a global online culture means that the younger artists have moved towards a more nuanced, multidisciplinary approach - Gallery

And in what ways is South East Asian culture in dialogue with that landscape?

Arts and cultural heritage are very much intertwined for those same reasons. A traditional romantic style is still practiced, alongside folk craft works. However, the rise of a global online culture means that the younger artists have moved towards a more nuanced approach to their practice, whilst also becoming more multidisciplinary.

Who are some of the most exciting artists in the region right now?

One to watch is Malaysia’s Haffendi Anuar. He was recognised initially as a sculptor, but is now moving towards painting and installation works taking on themes of religion and masculinity. There’s also Singapore’s WeiXin Quek Chong, an award-winning multidisciplinary artist taking on themes of tactility and sensoriality. She references the ASMR phenomenon in his work, as well as the self-care trend. We’re launching an online viewing room with her, entitled Digital Prelude, in September, with a physical solo show to follow at Cromwell Place in 2021.

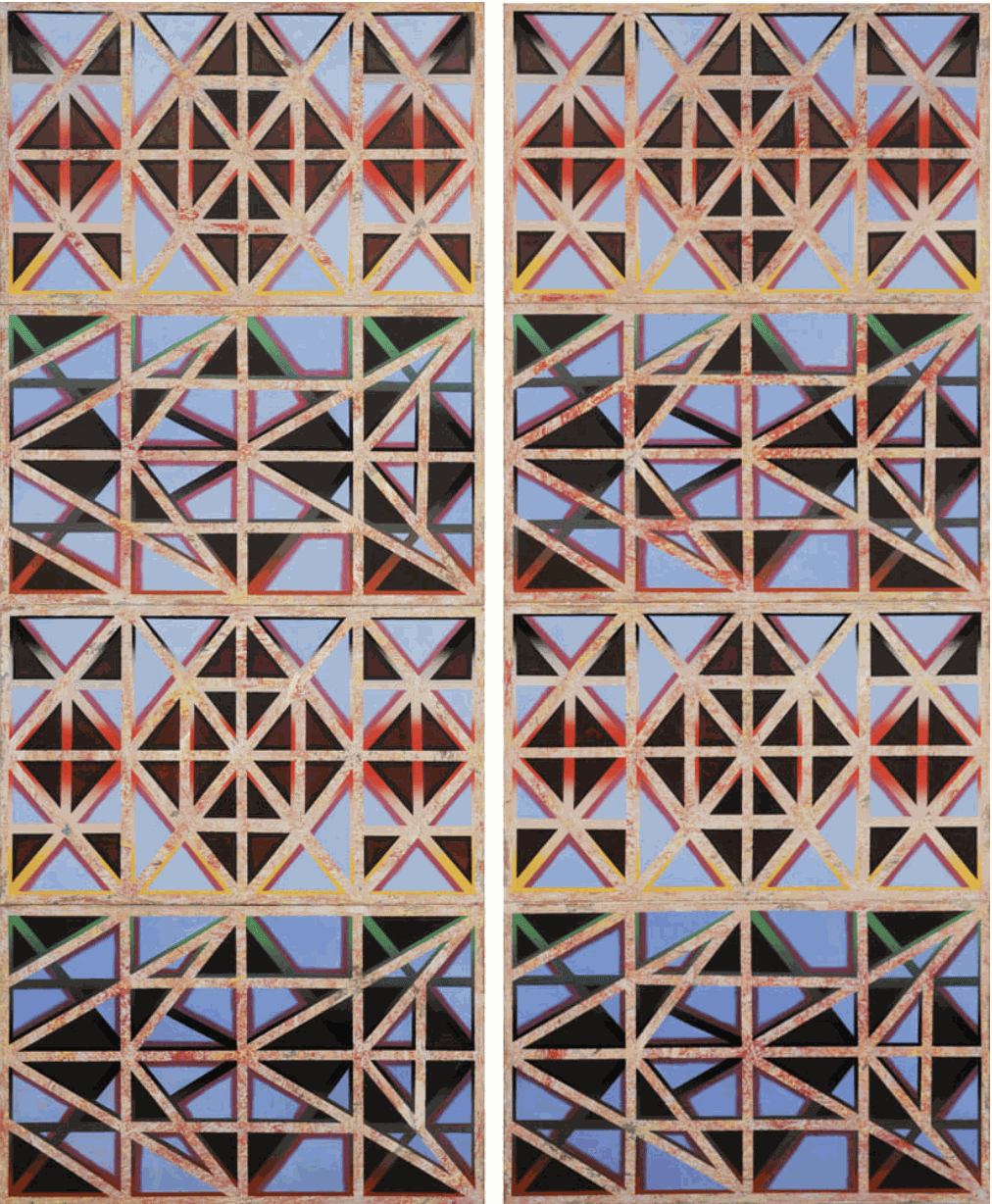

Haffendi Anuar, Out of the woods, 2016, Painting, oil and enamel on board, 199.5 x 80 cm each, set of two